Beyond Bills: How Members of Congress Can Use All of Their Tools

Updated February 18, 2025

Author: Catherine Rowland, Director of Government Access & Affairs

INTRODUCTION

This explainer highlights different tools members of Congress can use to hold corporations accountable, ensure the executive branch is following the letter of the law, raise awareness about key issues, build a Congressional record for long-term progress, and uphold our rights.

As the federal government’s legislative branch, Congress is best known for making laws. However, members of Congress have many more tools at their disposal that allow them to affect change without passing legislation. These tools are especially critical to members of Congress whose party does not control their chamber of Congress, since the party in control decides which bills advance and which do not. Understanding these tools is critical for the public, lawmakers, and advocates alike as they determine how to advance their priorities.

LETTERS

Any member of Congress concerned about a matter affecting their constituents, the country, or the world can author a letter raising the issue to relevant government officials or private sector actors. Letters are often made public, and members may invite their colleagues to sign them.

Often, members whose districts, states, or positions in Congress are directly related to an issue will organize a letter regarding that issue. For example, a member who sits on the House Committee on Transportation and Infrastructure—which conducts oversight concerning the Department of Transportation—would be well-positioned to author a letter to the Secretary of Transportation and may be more likely than other members to receive a timely and comprehensive response. However, a member need not sit on a particular committee to contact a government agency.

Members may also author letters on issues relevant to their constituencies or to them personally. For example, a member who owned a small business before running for Congress may wish to weigh in on small business loan regulations. Alternatively, a member whose relative lives with diabetes may be particularly inclined to question pharmaceutical companies about high insulin prices.

Letters serve an important purpose beyond the information they elicit in response: they offer members an opportunity to shine a light on the issue at hand, explain how it impacts their district and constituents, and drive news coverage of the problem. Letters can also garner public attention and, in turn, create pressure for the entity overseeing the issue—for example, the executive branch or a private company—to address it.

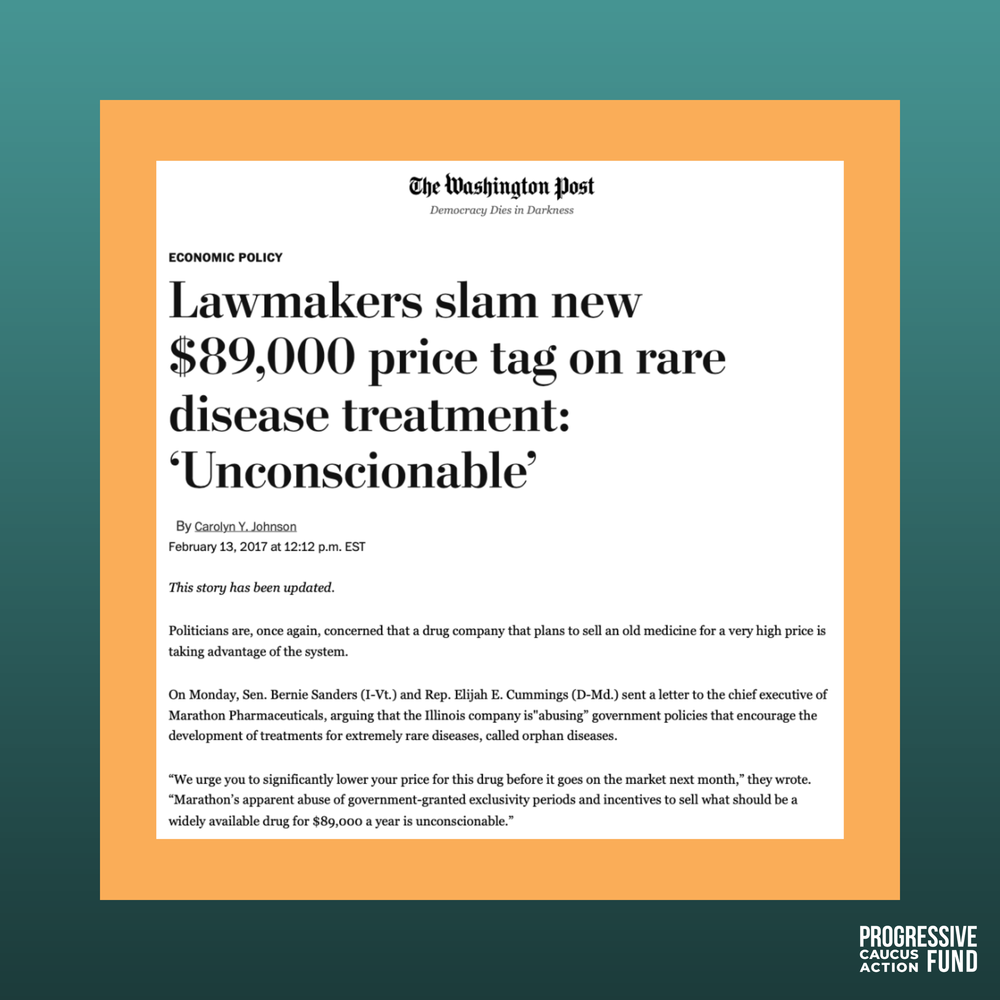

In the example below, Senator Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and the late Congressman Elijah E. Cummings (D-MD) penned a letter to a drug company CEO highlighting skyrocketing drug prices. Letters like this—and the subsequent news coverage—helped grow the salience of this issue over time and built public support for legislation to lower drug prices, like the Inflation Reduction Act (P.L. 117-169). This law allowed Medicare to negotiate with pharmaceutical companies to bring down drug prices for the first time in the program’s history.

One-on-one technical assistance for those ready to start creating and partnering on Direct Pay projects. We can help union leaders identify projects eligible for funding, walk you through the refund process, and help locals identify bridge funding.

Support for union negotiators interested in bringing Direct Pay to the bargaining table, including Direct Pay success stories and model contract language.

In some cases, members of Congress might author letters to each other—even members of the same party—to put their requests to one another “on the record.” For example, 18 House Republicans wrote to House Speaker Mike Johnson last year urging him to preserve the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy tax credits. A month later, the Speaker said he would be open to keeping some of those tax credits.

HEARINGS

Hearings are committee meetings during which members of Congress hear from witnesses on a predetermined topic and ask those witnesses questions. These meetings are typically open to the public and cover issues under the relevant committee’s jurisdiction. For example, a hearing about a foreign policy issue, like a military coup in another country, would be held in the House Foreign Affairs Committee or the Senate Foreign Relations Committee.

Hearings serve various purposes: they allow members to evaluate pending legislation, discuss a law’s implementation, conduct oversight over the executive branch or private industry, or learn more about an issue in the news. In early 2020, for example, numerous committees held hearings regarding the emerging coronavirus.

Hearings also provide a formal, public platform for members of Congress to bring attention to an issue and hear expert perspectives. The ability to organize committee hearings and select hearing topics is a privilege reserved for the majority party. However, members of either party can use hearings to highlight important issues and stories, call witnesses with various perspectives, and submit materials—including media reports and letters from outside organizations—for the record.

Moreover, the minority party can organize “shadow hearings” outside the official committee apparatus to draw attention to issues they feel the majority has neglected but, in their view, merit congressional action. For example, in 2023, the Democratic Women’s Caucus held a shadow hearing, “The State of Child Care in America: Addressing the Looming Funding Cliffs for Women and Families.” While such events might not appear in the congressional record, they can be opportunities for earned media coverage.

Members often use hearings to push for accountability and force witnesses to respond to inquiries on the record. Even if a member does not get a direct response to their questions, the very act of questioning can shed light on how a matter is being handled and indicate what steps those responsible for the matter might take next.

In the example below, former Congressman David Cicilline’s (D-RI) questioning of then-Secretary of Homeland Security Kirstjen Nielsen revealed that the Trump administration did not know how many people had died in the Department of Homeland Security’s custody. The public, in turn, could interpret that revelation as evidence that the administration had little regard for those people’s lives.

Members have also used hearing questions to this effect with private sector witnesses. In the example below, Congresswoman Pramila Jayapal (D-WA) questions Meta CEO Mark Zuckerberg regarding Facebook’s efforts to take over smaller companies. Viewers could interpret Zuckerberg’s failure to answer her questions directly as a tacit admission that Facebook used threats to acquire competitors.

In some cases, congressional hearings and other oversight actions can help build pressure on private companies to change their practices. In the mid-2010s, for example, Congress conducted numerous hearings as part of its investigations into the opioid crisis. These hearings generated media attention, in turn focusing greater public attention—and pressure—on the drug companies they targeted. Around the same time as Congress helped shine a spotlight on these companies’ contributions to the opioid crisis, some companies changed their practices. For example, in 2018, Purdue Pharma announced that they would stop marketing opioids to doctors.

Members may also use hearings to highlight broader issues shaping Congress’ agenda beyond the committee room. In the example below, Rep. Becca Balint (D-VT) confronts a GOP witness during a 2023 Oversight Committee hearing regarding environmental, social, and corporate governance-focused investing (ESG) after the witness alleged that ESG investment strategies support “forced gender transition for children.” Rep. Balint’s response pointed out House Republicans’ relentless scapegoating of trans youth, even during debates seemingly unrelated to the topic:

“It feels like every single hearing that I am in—whether it is in Oversight, or whether it is in Budget, or whether it is in a subcommittee—somehow the witnesses find a way to bring in trans children into whatever conversation we’re trying to have here.”

COMMITTEE INVESTIGATIONS AND REPORTS

An investigation or report from a member of Congress or congressional committee may not require action from a government or business entity but can highlight a matter of concern and, in turn, put pressure on the entity implicated to respond.

In some cases, a report can pressure other lawmakers to take—or not take—a specific action. For example, in 2017, the Democratic staff for the House Energy and Commerce Committee and the House Oversight and Government Reform Committee released a report outlining the consequences that repealing the Affordable Care Act (ACA) would have in every congressional district. The report came out as Republican members of Congress and the Trump administration were trying to pass ACA repeal legislation and detailed how many constituents in every district would be at risk of losing their health care under the proposed bill. Ultimately, while ACA repeal legislation eventually passed in the House, it failed in the Senate partly due to concerns over constituents losing their health insurance.

Notably, House Democrats released the aforementioned report while in the minority. While members in the majority may have additional resources at their disposal to conduct investigations or prepare reports, members do not need to be in the majority to compile reports like the one above.

PUBLIC STATEMENTS

A press release, press conference, social media post, op-ed, media interview, or other form of public statement by a member of Congress can help shape the narrative surrounding an issue or event.

Say, for example, an executive branch official makes an announcement or takes an executive action. Members of Congress might release statements offering their perspectives on that announcement or action—supportive or otherwise. The press may in turn include those perspectives when covering the executive’s moves, offering the public a more comprehensive picture of the matter at hand. This scenario plays out in the example below.

On February 4, 2025, President Trump proposed that the U.S. invade and “take over” Gaza. Numerous members of Congress quickly condemned the proposal, underscoring that such an invasion would be illegal and constitute ethnic cleansing. Such statements subsequently appeared in media coverage of the President’s remarks.

Floor Statements

Members of Congress often deliver statements from the House or Senate Floor to underscore the gravity of the issue at hand. In some cases, House members may organize a group of their colleagues to deliver statements about a specific topic on the House Floor during periods known as “special order hours.” These periods let members speak for longer windows than the House rules typically permit, allowing members to share stories and make more personalized appeals for specific bills or policies.

In the Senate, the majority leader may ask for unanimous consent to allow for “a period for transacting routine morning business” during which senators may speak on the Senate floor about their topic of choice. The length of these periods varies, depending on the Senate’s schedule.

AMICUS BRIEFS

Congress’ powers are distinct from the judiciary branch. However, the separation of powers does not preclude members of Congress from expressing their views on matters before the courts. Members may use an amicus brief—in which a person or group not party to a case before the court submits a public brief advocating for their favored outcome—to do this.

Members of Congress from both parties routinely submit amicus briefs to indicate and explain their positions on court cases. Whether or not the members’ brief influences the court, submitting an amicus brief can help the public better understand lawmakers’ positions on significant issues. Constituents may, in turn, hold their representatives to account should the same issue come before Congress in the future.

Members typically coordinate a single brief signed by a group of members with the same position. For example, in 2024, 263 members of Congress filed an amicus brief urging the Supreme Court to preserve access to the medication abortion drug mifepristone.

DIRECT ACTION

Site Visits

Members of Congress will sometimes visit sites where an issue of concern is occurring—and, in turn, draw media attention toward that site and issue. By generating news coverage, members’ site visits can build awareness of an issue and increase public pressure on the relevant stakeholders to address it. In 2019, for example, dozens of members of Congress made trips to the U.S.-Mexico border to examine the conditions in which immigration authorities were holding migrants. Their visits helped bolster the public’s understanding of the Trump administration’s immigration policies, including migrant children’s separation from their families.

Protests, Sit-Ins, and Rallies

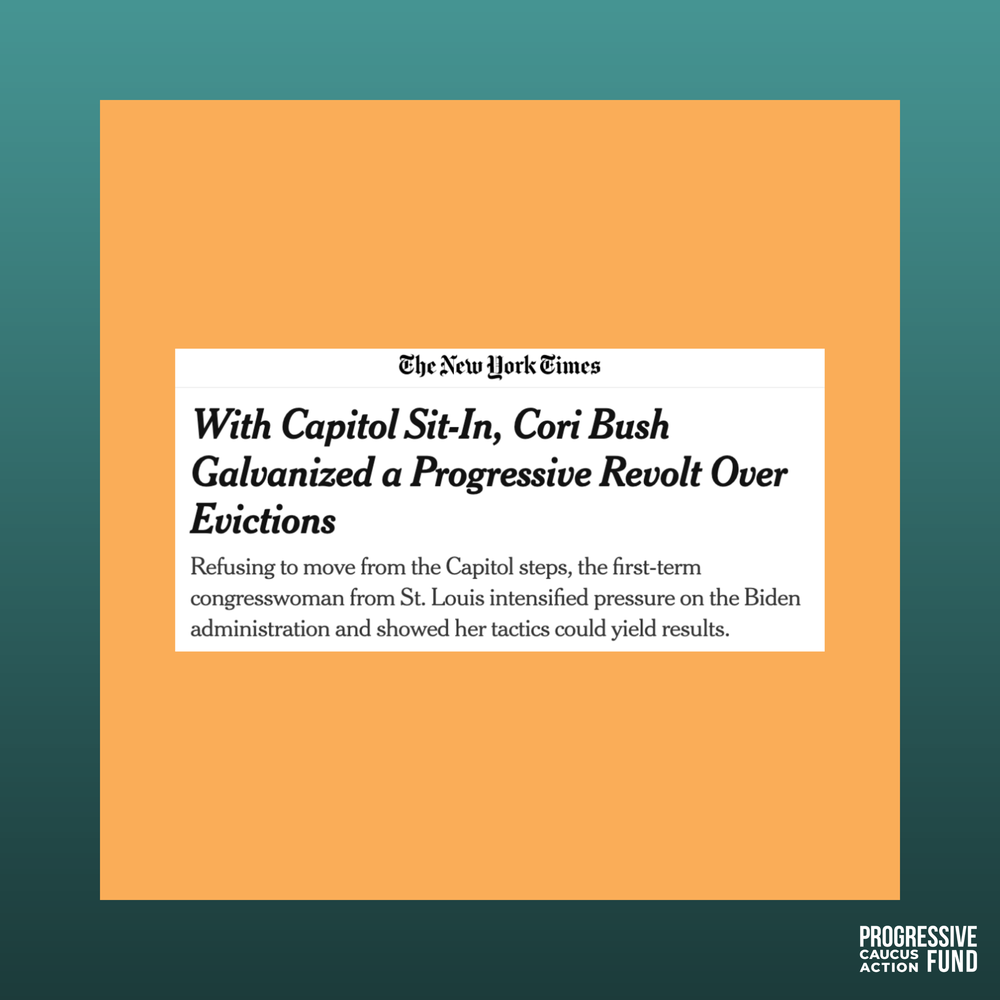

Members of Congress can also use their physical presence to affect change even when there is no “site” for them to visit. In 2021, Congresswoman Cori Bush (D-MO) began a sit-in on the U.S. Capitol steps and slept there to protest a federal eviction moratorium’s expiration. The Congresswoman’s direct action garnered tremendous attention and support for the eviction moratorium, which was extended within days.

Members may also attend protests or rallies that they do not organize personally. For example, in 2022, Senator Chris Murphy (D-CT) and other Senate Democrats attended a rally for gun violence prevention legislation outside the U.S. Capitol.

Some members have even engaged in non-violent civil disobedience. In July 2022, for example, after the Supreme Court struck down Roe v. Wade, 17 members were arrested during a protest in support of abortion rights.

CONCLUSION

Members of Congress have ample tools at their disposal that allow them to shine a light on important issues, demand accountability from government and private sector actors, and defend their constituents’ fundamental rights when they are under attack. Members retain these tools regardless of their party affiliation or seniority.

As such, Americans may demand action from their elected representatives no matter which party controls Congress. The tools and examples outlined in this explainer demonstrate that no individual member is powerless to affect change.